Most support tickets crossing our desks don’t warrant a blog article. However, occasionally we encounter a genuine mystery—a bug so pervasive and vile that it threatens innocent containers and pipelines everywhere. Such was the case of the OOM killer.

In this article, we alert our colleagues in the Nextflow community to the threat. We also discuss how to recognize the killer’s signature in case you find yourself dealing with a similar murder mystery in your own cluster or cloud.

To catch a killer

In mid-2022, Nextflow jobs began to mysteriously die. Containerized tasks were being struck down in the prime of life, seemingly at random. By November, the body count was beginning to mount: Out-of-memory (OOM) errors were everywhere we looked!

It became clear that we had a serial killer on our hands. Unfortunately, identifying a suspect turned out to be easier said than done. Nextflow is rather good at restarting failed containers after all, giving the killer a convenient alibi and plenty of places to hide. Sometimes, the killings went unnoticed, requiring forensic analysis of log files.

While we’ve made great strides, and the number of killings has dropped dramatically, the killer is still out there. In this article, we offer some tips that may prove helpful if the killer strikes in your environment.

Establishing an MO

Fortunately for our intrepid investigators, the killer exhibited a consistent modus operandi. Containerized jobs on Amazon EC2 were being killed due to out-of-memory (OOM) errors, even when plenty of memory was available on the container host. While we initially thought the killer was native to the AWS cloud, we later realized it could also strike in other locales.

What the killings had in common was that they tended to occur when Nextflow tasks copied large files from Amazon S3 to a container’s local file system via the AWS CLI. As some readers may know, Nextflow leverages the AWS CLI behind the scenes to facilitate data movement. The killer’s calling card was an [Errno 12] Cannot allocate memory message, causing the container to terminate with an exit status of 1.

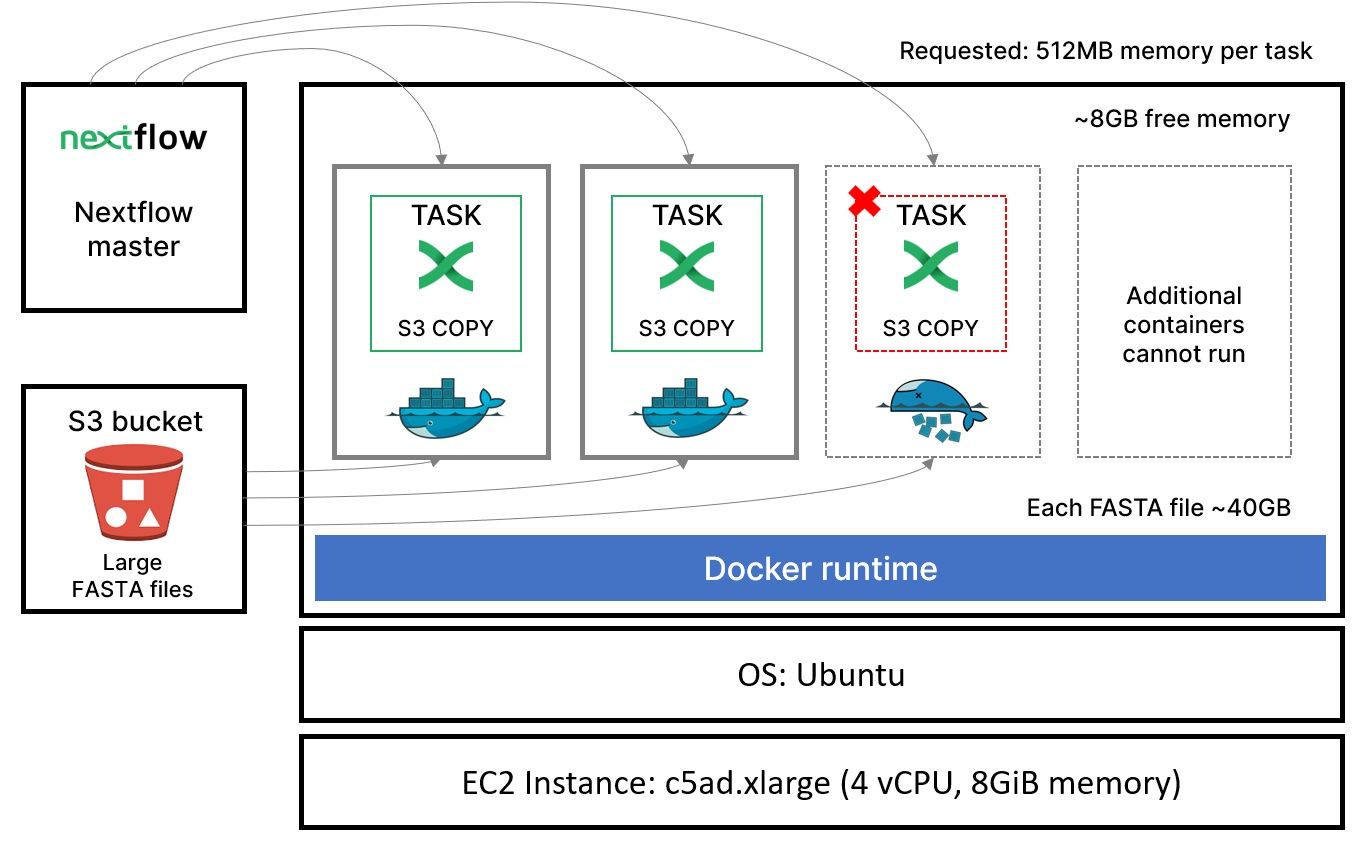

The problem is illustrated in the diagram below. In theory, Nextflow should have been able to dispatch multiple containerized tasks to a single host. However, tasks were being killed with out-of-memory errors even though plenty of memory was available. Rather than being able to run many containers per host, we could only run two or three and even that was dicey! Needless to say, this resulted in a dramatic loss of efficiency.

Among our crack team of investigators, alarm bells began to ring. We asked ourselves, “Could the killer be inside the house?” Was it possible that Nextflow was nefariously killing its own containerized tasks?

Before long, reports of similar mysterious deaths began to trickle in from other jurisdictions. It turned out that the killer had struck Cromwell also (see the police report here). We breathed a sigh of relief that we could rule out Nextflow as the culprit, but we still had a killer on the loose and a series of container murders to solve!

Recreating the scene of the crime

As any good detective knows, recreating the scene of the crime is a good place to start. It turned out that our killer had a profile and had been targeting containers processing large datasets since 2020. We came across an excellent codefresh.io article by Saffi Hartal, discussing similar murders and suggesting techniques to lure the killer out of hiding and protect the victims. Unfortunately, the suggested workaround of periodically clearing kernel buffers was impractical in our Nextflow pipeline scenario.

We borrowed the Python script from Saffi’s article designed to write huge files and simulate the issues we saw with the Linux buffer and page cache. Using this script, we hoped to replicate the conditions at the time of the murders.

Using separate SSH sessions to the same docker host, we manually launched the Python script from the command line to run in a Docker container, allocating 512MB of memory to each container. This was meant to simulate the behavior of the Nextflow head job dispatching multiple tasks to the same Docker host. We monitored memory usage as each container was started.

Sure enough, we found that containers began dying with out-of-memory errors. Sometimes we could run a single container, and sometimes we could run two. Containers died even though memory use was well under the cgroups-enforced maximum, as reported by docker stats. As containers ran, we also used the Linux free command to monitor memory usage and the combined memory used by kernel buffers and the page cache.

Developing a theory of the case

From our testing, we were able to clear both Nextflow and the AWS S3 copy facility since we could replicate the out-of-memory error in our controlled environment independent of both.

We had multiple theories of the case: Was it Colonel Mustard with an improper cgroups configuration? Was it Professor Plum and the size of the SWAP partition? Was it Mrs. Peacock running a Linux 5.20 kernel?

For the millennials and Gen Zs in the crowd, you can find a primer on the CLUE/Cluedo references here.

To make a long story short, we identified several suspects and conducted tests to clear each suspect one by one. Tests included the following:

- →We conducted tests with EBS vs. NVMe disk volumes to see if the error was related to page caches when using EBS. The problems persisted with NVMe but appeared to be much less severe.

- →We attempted to configure a swap partition as recommended in this AWS article, which discusses similar out-of-memory errors in Amazon ECS (used by AWS Batch). AWS provides good documentation on managing container swap space using the

--memory-swapswitch. You can learn more about how Docker manages swap space in the Docker documentation. - →Creating swap files on the Docker host and making swap available to containers using the switch

--memory-swap="1g"appeared to help, and we learned a lot in the process. Using this workaround we could reliably run 10 containers simultaneously, whereas previously, we could run only one or two. This was a good workaround for static clusters but wasn’t always helpful in cloud batch environments. Creating the swap partition requires root privileges, and in batch environments, where resources may be provisioned automatically, this could be difficult to implement. It also didn’t explain the root cause of why containers were being killed. - →

You can use the commands below to create a swap partition:

A break in the case!

On Nov 16th, we finally caught a break in the case. A hot tip from Seqera Lab’s own Jordi Deu-Pons, indicated the culprit may be lurking in the Linux kernel. He suggested hard coding limits for two Linux kernel parameters as follows:

While it may seem like a rather unusual and specific leap of brilliance, our tipster’s hypothesis was inspired by this kernel bug description. With this simple change, the reported memory usage for each container, as reported by docker stats, dropped dramatically. Suddenly, we could run as many containers simultaneously as physical memory would allow. It turns out that this was a regression bug that only manifested in newer versions of the Linux kernel.

By hardcoding these kernel parameters, we were limiting the number of dirty pages the kernel could hold before writing pages to disk. When these variables were not set, they defaulted to 0, and the default parameters dirty_ratio and dirty_bakground_ratio took effect instead.

In high-load conditions (such as data-intensive Nextflow pipeline tasks), processes accumulated dirty pages faster than the kernel could flush them to disk, eventually leading to the out-of-memory condition. By hard coding the dirty pages limit, we forced the kernel to flush the dirty pages to disk, thereby avoiding the bug. This also explained why the problem was less pronounced using NVMe storage, where flushing to disk occurred more quickly, thus mitigating the problem.

Further testing determined that the bug appeared reliably on the newer AMI Linux 2 AMI using the 5.10 kernel. The bug did not seem to appear when using the older Amazon Linux 2 AMI running the 4.14 kernel version.

We now had two solid strategies to resolve the problem and thwart our killer:

- →Create a swap partition and run containers with the

--memory-swapflag set. - →Set

dirty_bytesanddirty_background_byteskernel variables on the Docker host before launching the jobs.

The killer is (mostly) brought to justice

Avoiding the Linux 5.10 kernel was obviously not a viable option. The 5.10 kernel includes support for important processor architectures such as Intel® Ice Lake. This bug did not manifest earlier because, by default, AWS Batch was using ECS-optimized AMIs based on the 4.14 kernel. Further testing showed us that the killer could still appear in 4.14 environments, but the bug was harder to trigger.

We ended up working around the problem for Nextflow Tower users by tweaking the kernel parameters in the compute environment deployed by Tower Forge. This solution works reliably with AMIs based on both the 4.14 and 5.10 kernels. We considered adding a swap partition as this was another potential solution to the problem. However, we were concerned that this could have performance implications, particularly for customers running with EBS gp2 magnetic disk storage.

Interestingly, we also tested the Fusion v2 file system with NVMe disk. Using Fusion, we avoided the bug entirely on both kernel versions without needing to adjust kernel partitions or add a swap partition.

Some helpful investigative tools

If you find evidence of foul play in your cloud or cluster, here are some useful investigative tools you can use:

- →After manually starting a container, use docker stats to monitor the CPU and memory used by each container compared to available memory.

$ watch docker stats - →The Linux free utility is an excellent way to monitor memory usage. You can track total, used, and free memory and monitor the combined memory used by kernel buffers and page cache reported in the _buff/cache_ column.

$ free -h

After a container was killed, we executed the command below on the Docker host to confirm why the containerized Python script was killed.$ dmesg -T | grep -i ‘killed process’ - →We used the Linux htop command to monitor CPU and memory usage to check the results reported by Docker and double-check CPU and memory use.

- →You can use the command systemd-cgtop to validate group settings and ensure you are not running into arbitrary limits imposed by cgroups.

- →Related to the cgroups settings described above, you can inspect various memory-related limits directly from the file system. You can also use an alias to make the large numbers associated with cgroups parameters easier to read. For example:

$ alias n='numft --to=iec-i'

$ cat /sys/fs/cgroup/memory/docker/DOCKER_CONTAINER/memory.limit_in_bytes | n

512Mi

You can clear the kernel buffer and page cache that appears in the buff/cache columns reported by the Linuxfreecommand using either of these commands:$ echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches

$ sysctl -w vm.drop_caches=1

The bottom line

While we’ve come a long way in bringing the killer to justice, out-of-memory issues still crop up occasionally. It’s hard to say whether these are copycats, but you may still run up against this bug in a dark alley near you!

If you run into similar problems, hopefully, some of the suggestions offered above, such as tweaking kernel parameters or adding a swap partition on the Docker host, can help.

For some users, a good workaround is to use the Fusion file system instead of Nextflow’s conventional approach based on the AWS CLI. As explained above, the combination of more efficient data handling in Fusion and fast NVMe storage means that dirty pages are flushed more quickly, and containers are less likely to reach hard limits and exit with an out-of-memory error.

You can learn more about the Fusion file system by downloading the whitepaper Breakthrough performance and cost-efficiency with the new Fusion file system. If you encounter similar issues or have ideas to share, join the discussion on the Nextflow Slack channel.